The Arabian Nights. The Thousand and One Nights. One Thousand and One Arabian Nights. All of these titles serve as names for the fluid collection of Middle Eastern stories and folktales set in the framing narrative of storyteller Shahrazad to her husband, the king.

But let's back up a mo'.

Long, long ago (this is fictional), King Shahrayar got mad because his beloved wife cheated on him. He was such a wreck afterwards that, not only did he have his wife and her lover maimed and killed, but he vowed to continue the bloodbath. Every night, he married a new girl, bumped uglies with her, and killed her in the morning because EWWWWW! Girls are the WORST!!!!

His vizier was...conflicted. You see, contradicting a monarch in the Middle Ages anywhere was basically a death sentence, but perhaps most especially in this part of the world. The king had had such a tantrum over his wife's infidelity that he took it out on other -innocent- women every.single.day. It was just part of his journey.

Indeed, for the vizier to suggest some alternate form of frustration relief would have been risky...and he was a fan of his own head. Still, the vizier didn't like murdering innocent women and girls as part of his daily routine. But it wasn't until his own daughter made a suggestion that he was willing to do anything about it. Enter Shahrazad.

Shahrazad (often transliterated Scheherazade) was the eldest daughter of the vizier and she had an idea. A bright, intelligent, and clever girl, she proposed to her father that she marry the king. "QUOI?!?!?!?!?! Hard pass", said her dad, the vizier. No daughter of his was going to end up headless in the morning. But Shahrazad was persistent and insisted that she had a plan. Finally, her father reluctantly gave in, and granted her permission to marry the king. The king, confused by this turn of events, consented. His plans to kill her in the morning didn't change -and he made sure the vizier knew that- but he was curious to see where this whole thing was going.

After their wedding night festivities, Shahrazad began to cry. Upon asking her why she was crying (for real) the king learned that his newly doomed wife had a younger sister, Dinarzad, whom she wished to see once more before dying in the morning. So, King Shahrayar sent for Dinarzad to join them in the royal chambers. I mean, he was a He-Man Woman-Hater, not a monster.

After the "king had satisfied himself with her sister Shahrazad" (ew), Dinarzad awkwardly cleared her throat and suggested that Shahrazad tell one of her "lovely little tales to while away the night". She was, of course, not suggesting that her older sister tell campfire stories on the eve of her premeditated murder, but sticking to Shahrazad's well laid out plan. You see, Shahrazad was a great storyteller...and King Shahrayar loved story time even more than he hated women. Each night brought a new cliffhanger, so the king simply couldn't kill Shahrazad the next day or he'd never find out what happened next! This went on night after night, week after week, month after month...until the king finally grew to love Shahrazad and agreed not to kill her. Marital bliss.

It is this framing narrative that sets up every one of The Arabian Nights. Stories within stories within stories within a framing narrative (another story) often require a little bit of focus to keep everything and everyone straight. It's like the Middle Eastern folklore version of Inception. While there are technically only 271 nights in my translation (which is about standard), the notion of 1,001 nights is actually more of a colloquialism in the Arabic language, the number 1,000 often being used to represent an infinite number (of nights/stories, in this case). I was relieved when I learned this little factoid because (1) I couldn't find any translations that had 1,000+ nights and (2) I didn't want to read that many. The 271 nights that I do have amount to over 500 pages, which was honestly enough for me.

In my research on this collection of stories, I learned a lot of other things, too. For instance, many of the stories that we associate with The Arabian Nights (Alf Layla wa Layla, in Arabic) are not actually part of the original texts. The thing about The Arabian Nights is that they are almost as flexible as the Arthurian Legends or stories of Robin Hood. To find an "authentic original" is almost impossible as stories have been added and subtracted over the course of centuries. In fact, the well-known stories of Sinbad the Sailor, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and Aladdin were all added at later dates, some by European translators. While the tales Sinbad, Ali Baba, and Aladdin are all equally of Middle Eastern origin, they were not part of the earliest iterations of The Arabian Nights. For more on various translations, titles, and general information, check out this very thorough article: The Thousand and One Nights, Monica Mishra.

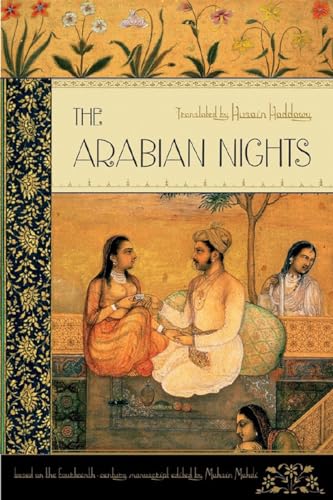

The translation I chose was by Husain Haddawy (copyright 1990), based on the fourteenth-century manuscript edited by Muhsin Mahdi. The Mahdi manuscript seems to be something of a gold standard among variations, but that's just based on my own amateur observations. Regardless, Haddawy's translation of this work is accessible and includes a very informative introduction by the translator about the evolution of the texts, manuscripts, and translations over the course of time. It also includes a handy map of the world of The Arabian Nights, that covers territory spanning from modern day Egypt to China.

The Arabian Nights are, in many ways, surprising. Prior to reading this translation, I had read a (very cleaned up!) children's version to my own kids a few years ago. What I didn't realize is how graphic, violent, raunchy, and racist the original texts were. While I wasn't surprised by the misogyny ("a woman needs either a husband or a tomb" -- or something like that), racism, and violence (they are of their time...), the sexual exploits and the ableism of the stories did leave me with my mouth agape. But the 13-year-old in me laughed wildly at the poop and penis jokes, while simultaneously cringing at the villagers openly mocking and bullying the poor hunchback.

Ultimately, The Arabian Nights transported me to A Whole New World (sorry, couldn't help it) of magic, fantasy, and some weird-ass shit. I laughed out loud, often having then to explain myself to others in the room; I winced at some of the ways the writers of these texts viewed the world; I rolled my eyes when "lovers" who knew each other for three hours had "affairs" (read: they looked at each other). But I had fun and, even if you don't read The Arabian Nights in their entirety, I would recommend reading at least a few of them as stand-alone stories. They are weird AF, but perhaps not as weird as the realities we experience every day.